Introduction to Python¶

This module introduces the fundamentals of Python programming language.

Content

- The course emphasises hands-on experience with Python in the UPPMAX environment. It focuses on the basics and can be taken by someone without any prior Python experience.

- You will learn:

- How to load and use different version of Python on our clusters

- Basic and more advanced builtin data types

- Using control flow statements to define the logic of your Python program

- Grouping code into reusable functions and structuring your program into modules

- Creating small command line programs that can take input arguments

- Reading and writing to files in Python

Schedule¶

| Time | Topic |

|---|---|

| 09:00-10:00 | Basic and Sequence data types |

| 10:00-10:15 | Break |

| 10:15-11:00 | Control flow statements |

| 11:00-12:00 | Exercises |

| 13:00-14:00 | Functions and Modules |

| 14:00-14:15 | Break |

| 14:15-15:00 | Command line arguments and IO |

| 15:00-15:15 | Break |

| 15:15-16:00 | Exercises |

What is Python?¶

- Developed by Guido van Rossum in the early 1990s

- Named after the British comedy group "Monty Python", not after the reptile

- Python is available for all operating systems for free

- Python is easy to learn (not master)

- Has a big ecosystem of packages for scientific computing

- Has a big community

- Commonly used in many scientific fields

Getting Started¶

Link to HackMd: https://hackmd.io/@dianai/uppmax-intro/

To work with Python on UPPMAX:

Login to Rackham¶

First, login to Rackham from your terminal. This is described at the UPPMAX page 'Login to Rackham' here.

How to login to Rackham from your terminal?

This is described at the UPPMAX page 'Login to Rackham' here.

Spoiler:

where [username] is your UPPMAX username, for example:

Load the Python module¶

Load Python version 3.10.8. This is described at the UPPMAX pages on Python here.

Pick how to work¶

There are multiple ways to develop Python code:

- Using Python scripts with a text editor

- Using the Python interpreter

- Using IPython

- Using Jupyter

We can work with Python either interactively or by writing our code into files

(so-called Python scripts) with the .py suffix.

Interactive "Hello, world!"

The canonical way of working interactively is using the Python interpreter which comes with the language. This is a so called REPL (read-eval-print loop) programming environment.

This will take you to the interpreter where you can start writing Python code (Think of it as a calculator for code).A read–eval–print loop (REPL), also termed an interactive toplevel or language shell, is a simple interactive computer programming environment that takes single user inputs, executes them, and returns the result to the user; a program written in a REPL environment is executed piecewise (wiki link).

Python 3.10.8 (main, Nov 15 2022, 21:16:40) [GCC 12.2.0] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> print("Hello, world!")

Hello, world!

>>>

We can use Python as a calculator. Try the following

A modern alternative is with more bells and whistles is

IPython. This is also the backbone of the very

popular Jupyter Notebook that you might be familiar

with. The "Hello, world!" example is completely analogous

And,

Python 3.10.8 (main, Nov 15 2022, 21:16:40) [GCC 12.2.0]

Type 'copyright', 'credits' or 'license' for more information

IPython 8.6.0 -- An enhanced Interactive Python. Type '?' for help.

In [1]: print("Hello, world!")

Hello, world!

In [2]:

We recommend using IPython for this course but you are welcome to choose

whatever you prefer!

- Anything that you can do in the Python interpreter you can also do in IPython

- I will likely use "Python interpreter" also to refer to IPython

- You can exit the interpreter with

exit(),quit()or pressingCtrl-D. - Tips and tricks of how to navigate IPython

Scripting "Hello, world!"

The interpreter is very handy if we want to test things out or need to work interactively, but, often what we want is to write an executable script or library that can be shared, documented and reused. Let's write a hello world script!

First create a file (module) called hello_world.py with your preferred editor

Next, write the same code as before

Save and close the file and then run the script from the command line

Variable assignment¶

Any and all values (objects) in Python can be assigned to a variable. As such Let's look at an example

In [1]: greeting = "Welcome to our Introductory Python Course!"

In [2]: print(greeting)

Welcome to our Introductory Python Course!

In [3]: number = 2

In [4]: print(number)

2

In [5]: number = 5

In [6]: print(number)

5

The name on the left-hand side now refers to the result of evaluating the right-hand side, regardless of what it referred to before (if anything). From discussion

Variable names

- Names of variables may be chosen freely, but

- must consist of a single word (no blanks)

- must not contain special characters except "_", and

- must not begin with a number

- Valid names are: my_variable, Value15

- Invalid names are: my-variable, 15th_value

Python Data Types¶

We will now try to understand some of the builtin data types - you will be

using these all the time. We will cover Int, Float, List, Bool and

String. If we have some spare time we might also have a look at Dict and

Set.

flowchart TD

A --- Numeric

A --- Boolean

A --- Dictionary

A --- Set

A[Fundamental builtin data types] --- Sequence

Numeric --- Integer

Numeric --- Float

Numeric --- Complex

Sequence --- String

Sequence --- List

Sequence --- TupleNumeric Datatypes¶

The table below shows some of the most common operations that work on numeric

data types (except complex). For more math functions see the

math module included in the

standard library as well as numpy and

scipy which are the cornerstones of scientific

computation in Python.

| Operation | Result |

|---|---|

x + y |

sum of x and y |

x - y |

difference of x and y |

x * y |

product of x and y |

x / y |

quotient of x and y |

x // y |

floored quotient of x and y |

x % y |

remainder of x / y |

x ** y |

x to the power of y |

abs(x) |

absolute value of x |

int(x) |

x converted to integer |

float(x) |

x converted to floating point |

| Source: Official Python docs |

Some examples

Let's try some example in ipython

Strings¶

Strings are a sequence data type representing unicode characters and is defined with single or double quotes.

We can actually several of the same operations we used for the numeric data type on strings.

String operations

In [1]: greeting1 = "Good Morning!"

In [2]: greeting2 = "Hello, How are you!"

In [3]: greeting1 + greeting2

Out[3]: 'Good Morning!Hello, How are you!'

In [4]: greeting = "Welcome to our Introductory Python Course!"

In [5]: number = 2

In [6]: greeting + number

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In [6], line 1

----> 1 greeting + number

TypeError: can only concatenate str (not "int") to str

In [7]: greeting + str(number)

Out[7]: 'Welcome to our Introductory Python Course!2'

In [8]: greeting = "Welcome to our Introductory Python Course!"

In [9]: number = 2

In [10]: greeting * number

Out[10]: 'Welcome to our Introductory Python Course!Welcome to our Introductory Python Course!'

In [11]: greeting = "Hello!\n"

In [12]: greeting * 8

Out[12]: 'Hello!\nHello!\nHello!\nHello!\nHello!\nHello!\nHello!\nHello!\n'

In [14]: print(greeting * 8)

Hello!

Hello!

Hello!

Hello!

Hello!

Hello!

Hello!

Hello!

Notice also that a string object has many associated methods. Try using the

.-notation to access methods (and attributes) by pressing tab.

In [3]: greeting1.

capitalize() endswith() index() isdigit() isspace() lower() removesuffix() rpartition() startswith() upper()

casefold() expandtabs() isalnum() isidentifier() istitle() lstrip() replace() rsplit() strip() zfill()

center() find() isalpha() islower() isupper() maketrans() rfind() rstrip() swapcase()

count() format() isascii() isnumeric() join() partition() rindex() split() title()

encode() format_map() isdecimal() isprintable() ljust() removeprefix() rjust() splitlines() translate()

String methods

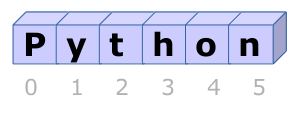

Remember that strings are sequences? This means that each character in a string has an index. We can use this to do all sorts of string slicing.

String indexing and slicing

In [1]: my_string = "This is a string"

In [2]: my_string[0]

Out[2]: 'T'

In [3]: len(my_string)

Out[3]: 16

In [4]: my_string[len(my_string) - 1]

Out[4]: 'g'

In [5]: my_string[len(my_string)]

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

IndexError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In [5], line 1

----> 1 my_string[len(my_string)]

IndexError: string index out of range

In [6]: my_string.index("i")

Out[6]: 2

In [7]: my_string[2:]

Out[7]: 'is is a string'

In [8]: my_string[-1]

Out[8]: 'g'

In [9]: my_string[-5:]

Out[9]: 'tring'

Lists¶

Just like String a List is a sequence data type. However, it is very

different. A list if is a sequence of elements (objects) of arbitrary type i.e.

we can have a list of strings a list of integers and a list of lists of

strings and integers. Let's start by looking at how can define a list

In [1]: list_of_ints = [1, 5, 2]

In [2]: list_of_str = ["hej", "du"]

In [3]: list_of_str == "hej du".split(" ")

Out[3]: True

In [4]: mixed_list = ["string", 3, True, []]

Notice how all the elements of the list are inside the square brackets [] and

how each element is separated by a comma ,. Lists are extremely useful, here

are some of the things you can do with them:

- Append new elements to the list

- Concatenate two (or more) lists

- Access individual elements by their index

- Perform some operation, reduction or transformation on all or some of elements in the list

Let's look at some examples

In [1]: l = []

In [2]: l.append(1)

In [3]: l

Out[3]: [1]

In [4]: l.append(2)

In [5]: l

Out[5]: [1, 2]

In [6]: m = [3, 4, 5]

In [7]: n = l + m

In [8]: n

Out[8]: [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

In [9]: n[3]

Out[9]: 4

In [10]: len(n)

Out[10]: 5

In [11]: sum(n)

Out[11]: 15

In [13]: min(l)

Out[13]: 3

In [14]: max(l)

Out[14]: 244

In [15]: sorted(l)

Out[15]: [3, 50, 170, 244]

In [16]: l.sort()

In [17]: l

Out[17]: [3, 50, 170, 244]

Control Flow Statements¶

- Control structures determine the logical flow of a program

- There are two types of key control structures in Python:

- Loops:

for,while - Conditions:

if-else

- Loops:

- These two types of control structures permit the modeling of all possible program flows

if-else conditions¶

An if statement is used to define a code block that is executed if a

condition evaluates to the boolean value True. The else statement is only

evaluated if the if statements is evaluated to False.

In [1]: my_boolean = True

In [2]: if my_boolean is True:

...: print("Michael, is it True?")

...: else:

...: print("No")

Michael, is it True?

In [3]: my_boolean = False

In [4]: if my_boolean is True:

...: print("Michael, is it True?")

...: else:

...: print("No")

No

Notice, we don't actually have to write ... is True. As we saw before

boolean operators are used to evaluate the identity of some condition. This

is very commonly used together with if statements.

In [1]: A = "ABCD"

In [2]: if len(A) <= 3:

...: print("Sequence A is smaller or equal than 3.")

...: elif len(A) > 3 and len(A) < 5:

...: print("Sequence A is greater than 3 and smaller than 5.")

...: elif len(A) == 5:

...: print("Sequence A is equal to 5.")

...: else:

...: print("Sequence A is greater than 5.")

Sequence A is greater than 3 and smaller than 5.

Indentation in Python

Control flow statements are always ended by a colon : and following lines

to be executed within the context statement must be indented by 4 spaces

(tab). Consider this program

Loops and iteration¶

Just like if-else statements, the idea of loops and iteration is

fundamental to Python (and any programming language).

The while loop¶

The while loop is conceptually similar to an if statement, but, instead of

executing the indented code block once - it's repeated as long as the

statement evaluates to True. Can you guess when the following examples are

going to stop?

Answer

It will continue continue for eternity.

Answer

It will print "Hello, world!" 10 times before stopping

Answer

It will stop in the first iteration. The keyword break will break out

from any loop.

And last one...

Answer

v1 goes to infinity and v2 stops after 10 iterations.

The for loop¶

The for loop is typically used when looping "over" something. Formally, a

for loop can be used over any object that is iterable and implements a

iter and next method - like a list, string, set or range. Let's look at an

example by looping over the string "ABCD"

We can also use for loops over lists

and ranges defined by the builtin range function

Iterables and why for loops sort of are while loops?!

If an object is iterable - we can always create an iterator object with

the iter function. This is what the for keywords does under the hood.

In [1]: my_string = "ABCD"

In [2]: type(my_string)

Out[2]: str

In [3]: my_string_iterator = iter("ABCD")

In [4]: type(my_string_iterator)

Out[4]: str_iterator

In [5]: next(my_string_iterator)

Out[5]: 'A'

In [6]: next(my_string_iterator)

Out[6]: 'B'

In [7]: next(my_string_iterator)

Out[7]: 'C'

In [8]: next(my_string_iterator)

Out[8]: 'D'

In [9]: next(my_string_iterator)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

StopIteration Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In [9], line 1

----> 1 next(my_string_iterator)

StopIteration:

As seen from above - we can coninue calling the next function to get the

next element of the string iterator object until the iterator is

consumed. The way a for loop is implemented is loosely something like

this

If you still need the index of the current iteration refrain from using the

range(len(seq)) idiom and use the enumerate function instead.

Just like we nested an if statement into a loop before we can also nest a

loop within a loop.

When should I use for and when should i use while?

As a rule of thumb - use for loops when dealing with iterable objects

(ranges, sequences, generators). Another way of thinking about it is, use a

for loop when the number of iterations e.g. length of sequence is known.

In other case - use a while loop (you have to).

Links¶

- YouTube video on

pythonversusIPython - YouTube video on

IPython - Previous content is adapted (and extended) from previous iterations of the course and slides developed by Nina Fischer (see slide deck one and slide deck two).